November 21, 2017

Seema Verma, Administrator

Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services

7500 Security Blvd.

Baltimore, MD, 21244

Attention: CMS-9930-P

Dear Administrator Verma:

Thank you for the opportunity to comment on proposed Benefit and Payment Parameters for Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act plans in 2019.

Accreditation for Network Adequacy: The National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) appreciates the proposal to rely on private sector accreditation for network adequacy. However, only Exchange plan accreditation should qualify. Accepting issuers’ Medicaid or commercial plan accreditation, as proposed, would not be sufficient, as networks for Exchange, Medicaid and commercial offerings from the same issuers are often substantially different.

NCQA has taken several steps to strengthen network standards for Marketplace offerings to address concerns about the high prevalence of narrow network plans. These include:

- Transparency: Requiring issuers to explain the criteria used for establishing narrow network provider selection, and to place that explanation near the provider directory.

- Monitoring: Requiring issuers to monitor and analyze complaints, appeals and out-of-network service requests to identify and address any potential shortcomings in their networks.

- Directories: Requiring updates within 30 calendar days of receiving new information from network physicians, and annually evaluating and acting to improve directory accuracy.

These are in addition to long-standing network requirements, such as requiring plans to:

- Maintain adequate networks of primary, behavioral and specialty care clinicians and assess whether they meet their members’ cultural, ethnic, racial and linguistic needs, with special focus on high-volume or high impact specialties such as obstetrics/gynecology and oncology.

- Establish and analyze performance against measurable standards for each of the above categories of clinician and their geographic distribution.

- Collect and analyze performance against access standards for routine, urgent after-hours and behavioral care.

- Prioritize, implement and measure impact of interventions to make improvements.

- Notify members 30 days before terminating providers, and allowing up to 90 calendar days continued access for patients in active treatment with them.

We list our health plan accreditation requirements on our NCQA website. We offer detailed specifications for sale to plans seeking accreditation, and for free to government, academic, consumer advocate and other stakeholders upon request. We also share results with government agencies to support plan oversight.

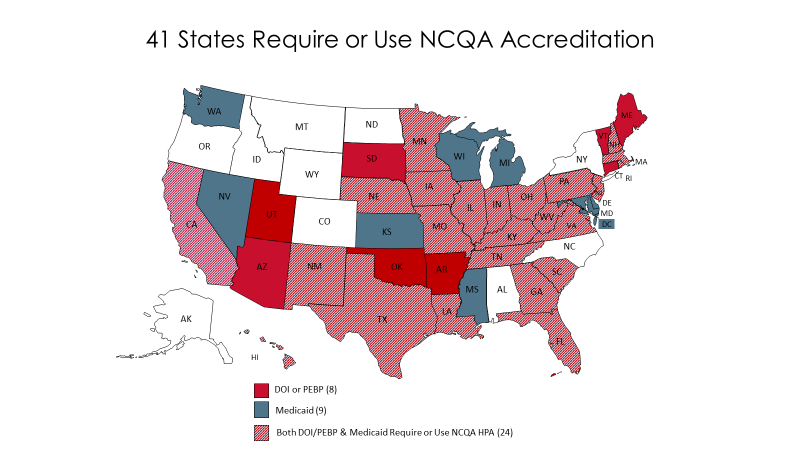

State Review: Deferring to state review of accreditation requirements, compliance reviews, minimum geographic service area & quality improvement strategy reporting, as proposed, has some risk. It could also enhance reliance on private accreditation and thus further reduce burden on plans and states. State review could lead to uneven enforcement of key requirements and protections for people in ACA plans. However, this policy could simplify review in states that already rely on accreditation. Currently, 41 states recognize NCQA Accreditation in whole or part for their commercial and/or Medicaid plans, and most Exchange plans have NCQA accreditation. The 33 states that rely on NCQA Accreditation for Medicaid plans, for example, could share Exchange quality improvement strategy reporting with Medicaid agency staff who are already familiar with these responsibilities.

Social Risk Factors: We appreciate the need to address socioeconomic factors that can impact quality in reporting of quality data. However, the best way to do this is by stratifying results by socioeconomic status of patients within affected measures. This approach highlights disparities, showing plans which subpopulations among their enrollees most need targeted quality improvement efforts.

We have begun doing this on four of our HEDIS®[1] quality measures on which there are persistent socio-economic disparities (Colorectal Cancer Screening, Breast Cancer Screening, Diabetes Care – Eye Exam, and Plan All-Cause Readmission).

We strongly oppose risk adjusting measures themselves for social risk factors, as this merely hides disparities without encouraging needed action to address them. We instead support risk adjusting payments to plans to account for the higher costs associated caring for people with lower socioeconomic status, as CMS is doing in the Medicare Advantage program.

Medical Loss Ratio: We do not support the proposal to let issuers report a single quality improvement activity expense amount equal to 0.8% of earned premium in lieu of reporting the actual quality improvement activity amounts in five specific categories. This would give plans spending less on essential quality improvement activities unearned credit and thus discourage both meaningful and innovative quality improvement efforts.

Essential Benefits: We do not support the proposal to allow states to impose non-dollar limits, such as on the number of visits, on specific benefits. We appreciate the intent here to reduce premiums, but believe that is short-sighted. Long-term increased cost for preventable problems that result from arbitrary limits not based on individual patients’ actual medical needs would dwarf any short-term savings such a policy might yield.

Risk Adjustment Transfers: We also do not support letting states request up to a 50% adjustment in calculating transfer amounts. This would reduce amounts transferred from plans with healthier populations to those with sicker enrollees, undermine the affordability of plans with sicker patients, and ultimately encourage plans to once again try to compete by avoiding sicker patients.

Cost-Sharing and Value-Based Insurance Design: We strongly support value-based insurance design, which reduces or eliminates cost sharing for high-value services and providers. Current law incorporates this by requiring no cost-sharing for preventive services that have high ratings from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. We believe VBID should also extend to at least two more important areas:

- Medications and other essential services for high-quality management of chronic diseases. Removing financial barriers to diabetes drugs, for example, helped Pitney Bowes reduce emergency room visits by 26%, with even greater savings over time.

- Clinicians meeting NCQA’s or similarly rigorous standards for Patient-Centered Medical Homes (PCMHs) and Patient-Centered Specialty Practices (PCSPs). A growing body of evidence documents that patient-centered care improves outcomes by promoting more evidence-based care, preventive services and good chronic care management. It also reduces costs by preventing avoidable hospital admissions and emergency department visits. Cutting cost sharing for enrollees who use PCMHs and PCSPs should thus improve quality and save money for enrollees, plans and taxpayers alike.

These VBID expansions could help mitigate potential harm from high-deductible health plans that, as currently structured, discourage both high and low-value health care.

Thank you again for considering our comments. If you have questions, please contact Paul Cotton, Director of Federal Affairs, at cotton@ncqa.org or (202) 955-5162.

Sincerely

Margaret O’Kane

President

[1] HEDIS – the Healthcare Effectiveness Data & Information Set, is a registered trademark of NCQA.