The Quality Doctor as Alzheimer’s Advocate

June 14, 2022 · Matt Brock

One way to honor Alzheimer’s and Brain Awareness Month in June is to share personal accounts. NCQA’s Executive Vice President, Eric Schneider, MD, MSc, offered these thoughtful remarks at a recent conference hosted by the National Academies, “Organizational Behavior Change to Address the Needs of People Living with Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias.”

We thank the Academies for the opportunity. Eric’s remarks have been lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

I’m here today, in part, as the son of a person with dementia.

In 2019, just after moving with my father into an independent living apartment connected to a nursing facility, my stepmother was widowed.

By 2021 we were in the middle of a pandemic, and she found it increasingly hard to participate in our Zoom calls. When we finally were allowed to visit in August, we found she had become meek and passive.

We’d hoped these setbacks were just pandemic isolation, but she was becoming more withdrawn, more frail, and had started to repeat herself.

She moved out of independent living and into a personal care unit in the nursing facility. Her agitation increased, in part because she was no longer in her apartment. She was prescribed meds that led to low sodium, acute delirium and hospitalization. She never received a full neurologic evaluation.

She was discharged from the hospital to a rehabilitation facility, with ongoing delirium. I warned the staff that she was not back to baseline. They prescribed benzodiazepine, which increased her agitation and made her combative. She ended up back in the hospital within a week. After more evaluation—still no neurologic evaluation—they discontinued the medication and she resolved.

When I was visiting her a couple of weeks later, a nurse said to me, “She seems agitated. We’re thinking we should start her on Lexapro.” The nurse was unaware of what had happened, even though it had caused dramatic problems.

My stepmother’s delirium cleared after several months, but the memory problems were worse. She finally got a neurologic evaluation—and I had to call several times to get the results.

Lessons Learned

I’d experienced situations like my stepmother’s in my own practice as a primary care doctor, but to live it from the caregiver side has been eye-opening.

- Early intervention is important but hard: It’s difficult to recognize memory loss early, and one consequence is that staff often frame “bad behavior” as willful, rather than as a manifestation of disease.

- People who know get ignored: I’ve known my stepmother a long time, can discern a lot over the phone and have relevant training. The staff at my stepmother’s facility are excellent, but often my observations were disregarded and didn’t seem to matter.

- The rural access crisis is real: Getting a neuropsychiatric evaluation in places like Boston, where I practiced for years, was hard. But that was nothing compared to getting one in rural Pennsylvania. Access in rural areas is at crisis levels.

The Problem of Coordination

More than anything, the problem highlighted by my stepmother’s experiences was one of coordination. Organization-specific quality models don’t get to the heart of quality problems for persons with dementia or other chronic diseases. From the patient’s perspective, the root of the quality gaps is poor coordination among organizations and clinicians.

I’m a physician, but it was incredibly difficult figuring out how to get through to my stepmother’s primary care physician or to communicate with specialists—to the extent I could even find specialists. I’m still trying to figure out her health insurance and what it covers, and what it may not cover.

We’ve made great strides in improving primary care, through teamwork, the patient-centered medical home model of care and the payment models CMS has created. I think if we could improve nursing home quality, that would be fantastic.

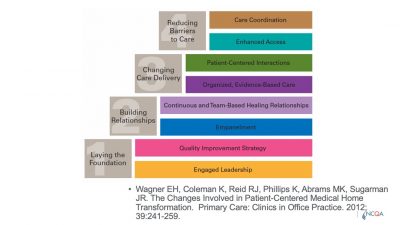

This figure (Wagner et al., 2012) points out that there’s a need to develop capabilities, starting with a foundation of [quality improvement] strategy and engaged leadership. The top layer is where care coordination happens.

This figure (Wagner et al., 2012) points out that there’s a need to develop capabilities, starting with a foundation of [quality improvement] strategy and engaged leadership. The top layer is where care coordination happens.

Quality Accountability Imperatives

I want to point out some quality and accountability imperatives for people living with dementia.

- Situational awareness is something we don’t emphasize enough in our quality measurement systems. For years, we’ve relied on claims. They lag 3 months, they lag 6 months. You can’t effectively date or time stamp anything. It’s hard to understand the sequence of events in the journey of any one patient or set of caregivers, to get true situational awareness.

That requires a capability to exchange data quickly, to be able to identify problems and share information. At the top of situational awareness must be caregiver support. For people with dementia—even with early symptoms and signs—transitions are incredibly difficult to manage, as I’ve seen now, [with my stepmother]. It’s also crucial to know if services are accessible or not.

- This issue of safety is critical. My stepmother had at least two avoidable hospitalizations. It’s true that there were challenges around fall prevention, but [the facility staff] restricted and frustrated her in ways that were probably unnecessary. We have to be mindful that our quality metrics don’t create incentives for staff to act in ways that are counterproductive for people with dementia.

- Focus on intermediate health outcomes. Functional status, cognitive ability, being able to monitor behavioral cognitive issues in real time—our systems don’t do well. We should think less about clinical measures based on clinical guidelines and think more about goal-directed outcomes and measurements.

- Communication between caregiver and care team is going to need new administration approaches, because our surveys are not timely enough.

- Sharing and measuring information is something other industries do remarkably well with their digital systems, but it requires a data infrastructure we currently don’t have. We’re operating a national air transportation system without air traffic control. We just don’t think about our systems’ design the way that other industries think about using data to coordinate logistics.

- When I was closing up my stepmother’s apartment, I was struck by the non-stop telemarketer calls, and I realized telemarketers know she’s vulnerable. They have identified her. What would it take for our health care system to be equally sensitive to predicting the needs and wants of people who are developing dementia? The telemarketers do it better than we’re doing it.

What Else Might Need to Change?

NCQA is focused on the expanded use of electronic data. There are some good tailwinds our work can operate on.

- The Cures Act and the regulations around data exchange interoperability will set the foundation for a capability that could support some of what I’ve described.

- Nobody seems to know how the broadband investment—$65 billion—is being spent in states. It somehow slipped under the radar. States have the opportunity to tie that broadband funding to issues like nursing homes and community-based organizations.

There’s a temptation now—as there has been for 20 years—to say, “If we change payment and payment incentives, that will lead to the changes we want to see in the system.” But those changes aren’t going to be enough to drive the kind of digital infrastructure reengineering, systems reengineering and organizational improvement we hope to see.

I would remind you to think about what else might need to change in the infrastructure and what other investments might be needed to maximize the return on investment for these payment model changes.